The Mysterious Disappearance of Influenza

A review of the reasons to believe that the flu really did vanish during the pandemic.

Yesterday, CDC advisers voted unanimously to add Corona vaccines to child immunisation schedules, and today the European Medicines Agency approved Pfizer/BioNTech and Moderna vaccines for use in infants in the European Union. I find these developments too depressing to discuss. The doses administered under these rules will kill a small but nontrivial number of children in exchange for nothing at all. That the vaccines don’t prevent transmission, that children are at zero risk from Omicron infection, that all of this pointless – none of this matters. Making these arguments is like talking to a wall for all the effect that it has.

Instead of boring you with the obvious, I want to return to a phenomenon I’ve alluded to a few times now, namely the disappearance of influenza during the pandemic. Every time I mention this, the commentariat voice their scepticism, and I’ve long planned a single post explaining my reasons for thinking a) that influenza really did disappear in 2020 and 2021; b) that this had nothing to do with lockdowns and everything to do with the emergence of a new pathogen and its disturbance of the broader virological ecosystem; and c) that we cannot so easily put this vanishing act down to shifts in testing or diagnosis caused by Coronasteria. To prove these points I’ll use German data, which I’m the most familiar with, but you could argue similarly with CDC numbers, or the statistics of many other countries.

That lockdowns aren’t the reason influenza disappeared is the easiest case to make. Influenza vanished even in countries that never implemented heavy containment measures, like Sweden and Taiwan. Other viruses, meanwhile, like RSV, persisted in open countries, while taking a heavy hit in lockdown-happy regions like Europe. There’s a twofold phenomenon at work here: Lockdowns were just effective enough to hurt the slower-moving mostly harmless viruses we’ve lived with for centuries, but influenza disappeared in almost all jurisdictions, whether they locked down or not. Nor is the vast reduction in international travel a credible reason for the disappearance of flu: Seasonal outbreaks have been a regular occurrence since the 1918 pandemic, when comparative mobility rates were very low indeed.

The disappearance of influenza is also not a mere artefact of testing, or of unreliable PCR tests misdiagnosing the flu as SARS-2, and of this I have two proofs.

The first is influenza surveillance data from before and during the pandemic. Participating sentinel clinics swab patients with respiratory symptoms, and send these swabs to a central testing facility. Each swab is tested for all of the major respiratory viruses.

Here’s the results of this virus survey from the 2018/19 season, by week number:

Red is influenza, yellow is RSV, purplish grey (?) is adenovirus, blue is rhinovirus, and green is human metapneumovirus. The grey bars in the background are the numbers of swabs tested; the prevalence of each virus is expressed as a positivity rate.

Yes, you will say, these statistics are bad, but we just a want a rough idea. There are three patterns to notice:

1) Rhinovirus peaks in the fall and the spring. Thus rhinovirus infections are in (relative) decline for the whole space of this graph.

2) RSV and adenovirus and some of the other common respiratory viruses peak around the winter solstice or just after. Unfortunately, the Robert Koch Institut didn’t track hCoVs in the 2018/19 season, but here’s a recent American paper establishing that, indeed, they have roughly the same peak in January or early February – with the interesting exception of 2020/21, when containment measures plausibly delayed the season:

3) The ordinary influenza peak follows the peak of these winter solstice viruses.

It looks for all the world like virus seasonality is driven mostly by two phenomena: The dark winter months, which create a greater potential for infection; and the apparent interference of viruses with each other. Why do rhinoviruses decline in the fall? Probably because this is when the solstice viruses are on the rise. Why does influenza have peak so late? Perhaps because it has to wait until the solistice viruses have ebbed sufficiently.

Now have a look at the equivalent 2020/21 season report from the middle of the pandemic. It couldn’t be more different:

The sentinel clinics continued testing for influenza, and none of the swabs they tested came back positive for influenza. They found only a few ordinary human-infecting coronaviruses, relatively normal levels of rhinovirus, and SARS-2. Influenza was gone.

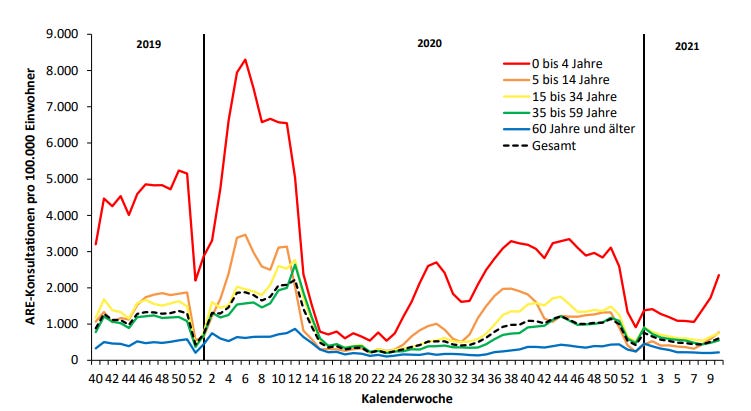

Now for the second proof, which is even more powerful than the surveillance data, and defeats a lot of the objections that might be raised against it. Flu is different from SARS-2 and ordinary human coronaviruses, in that it’s also somewhat dangerous for infants and kids under four years old. Thus, a lot of kids get taken to the doctor every flu season. Here’s the consultation incidence for acute respiratory infections, by age group, for the 2017/18 and 2018/19 flu seasons:

The red line is kids under four. Kids get a little sicker into the Fall, but they’re never brought to the doctor with such frequency as during the post-solstice height of flu season in February.

Now compare the same chart of consultation incidences for the 2020/21 pandemic season:

Young kids saw their doctors at vastly lower rates during the pandemic because influenza wasn’t around to infect them.

The hospitalisation data show the same thing. Here’s a chart of everyone who spent at least a week in hospital for a severe acute respiratory infection since the 2018/19 season:

The red line is again kids under four. They went from being the most hospitalised age-bracket in the pre-pandemic years, to being one of the least-hospitalised groups during the Corona freakout.

As I typed above, I don’t think lockdowns can take the credit for this, because influenza disappeared everywhere, even in countries that didn’t lock down.

Why then, did influenza disappear?

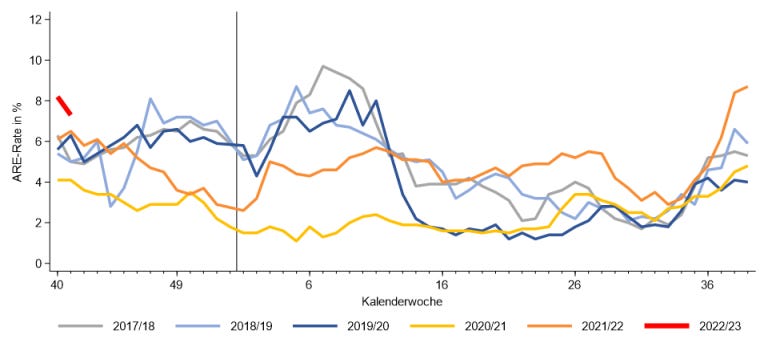

Let’s start with one of my favourite datapoints of the whole pandemic, the German fever gauge called Grippe Web. Hundreds of thousands of volunteers submit regular surveys about the presence or absence of respiratory symptoms, and the aggregated data can be used to estimate the rate of acute respiratory infection across the whole population:

The pandemic was a period of atypically low infections. Otherwise, while infections are higher than usual right now, they never exceed about 10% of the entire population. Our current Omicron wave, in fact, began to recede precisely as the fever gauge broke 8%. It’s almost as if there’s an upper limit on the number of people who can fall ill at any given time, and that waves of virus infection recede when they’ve reached this limit.

A second clue can be found in the case curves for the first three waves:

Germany here is entirely typical; many countries showed a similar pattern. Note that the second wave peaked precisely in the solstice-virus season, where we would expect a human-infecting coronavirus to be most advantaged, while the third wave peaked perfectly in influenza season. Pre-Omicron SARS-2 appropriated flu season for itself, while remaining dominant in its own solstice niche as well.

Many theories are possible, but this much seems true, at a purely descriptive level: Only a minority of the population – 10% or fewer – are susceptible to respiratory virus infection at any given time, and many viruses simply can’t surge if others are active. A nontrivial number of people who have recovered from one infection are removed the pool of potential hosts for weeks or even months afterwards. SARS-2 defeated influenza, probably, by outcompeting it for those few hosts who remained susceptible late in the 2019/20 season. Lockdowns probably helped SARS-2 to gain prominence, by wiping out some of its less contagious competitors, including spring rhinoviruses. Influenza has only begun to return with Omicron, which behaves much more like an ordinary human-infecting coronavirus and cannot exclude influenza infection as completely.

I'm still never getting a flu shot.

Interesting. And just a quick note regarding the vaccine developments too depressing to discuss. I hear you and understand, Eugyppius. But please know that as a parent your voice has been so helpful in beating back social pressure and assisting in my ability to articulate the valid concerns about the “vaccines.” I know for a fact that my influence and example in my social circle has given other parents the courage to avoid vaccinating their children. And for those that did so anyway, almost no one I know is keen on the boosters. So while your work may not yet impact the corrupt vaccine decision makers, it is an important component of opening minds and may be literally saving lives.

Finally, please see Jordan Schachtel’s piece regarding why the “vaccines” have been added to the US child immunization schedules. It is all about granting permanent legal immunity to Pfizer and Moderna, and all injuries will now be under the purview of the federal government.

https://dossier.substack.com/p/the-cdc-will-vote-thursday-to-permanently