The Terrifying Vacuity of Klaus Schwab

A review of COVID-19: The Great Reset, one of the dumbest, most tedious and utterly pointless books ever written.

Klaus Schwab and Thierry Malleret, COVID-19: The Great Reset (Forum Press: Cologny/Geneva, 2020). 280 pp.

Like many bad books, The Great Reset lapses into occasional inadvertent autobiography. In the final pages especially, where Klaus Schwab writes of his hopes for a “Personal Reset” through state repression, we catch a glimpse of the man during the first-wave lockdown at his house in Cologny. At first he enjoyed the break with routine and the opportunity to commune with nature, but before long he began to feel a nagging unease. He’d spent most of his years prior to 2020 flogging “stakeholder capitalism”, his umbrella term for various schemes to disarm criticism of the globalist corporate borg and co-opt leftist opposition. Schwab succeeded in parlaying his simplistic ideas into an international conference circuit, known today as the World Economic Forum, where he could hobnob with corporate and political celebrities and burnish his Bond-villain reputation among political dissidents. But the pandemic had thrown Schwab off balance. For once his reprocessed nostrums about environmental, social and corporate governance issues were no longer in demand; virologists and epidemiologists and exponential growth curves filled the news instead. His powerful celebrity clients were suddenly listening to other people. Obscurity loomed.

Thus Schwab enlisted his sidekick research-assistant Thierry Malleret, booted up his laptop, and spent a few months decanting the cloud of buzzwords, talking points and half-remembered powerpoint presentations plaguing his brain into a meandering and thoroughly pointless document. When he had finished, he sent the whole thing to Malleret’s wife for a proof-read, and then he ordered his own Forum Press to print off a few thousand copies. Thus did yet another lamentable exercise in self-publishing come to pass.

The Great Reset is not a book that begins with a fully-formed argument, which it seeks to articulate through successive proofs. Nor is it a book that finds its purpose along the way. It is of that still more miserable variety, that is always on the verge of discovering what it means to say, but can never quite get there. I have a vision of Schwab in his study, typing furiously with extended index fingers like a bicephalic chicken, marshalling all his meagre powers to reconstruct the very unexpected pandemic in which he found himself, such that it might better resemble the kind of global ESG stakeholder capitalism woo crisis that Schwab would really prefer to pronounce upon. “We must get back to my pet themes” is what Schwab is trying to tell us in The Great Reset. It is above all a childish book.

Schwab’s core idea is that the pandemic will either remake or reset our world, and thus political and corporate leaders have before them a unique opportunity to Build Back Better and make everything more ESG-compliant. All that’s clear enough, but for a man who put the word “reset” in his title, he seems strangely undecided on what the nature of this reset might be, and what role the virus had in bringing it about.

In the introduction, for example, we find this string of absurdities:

Many of us are pondering when things will return to normal. The short response is: never. Nothing will ever return to the “broken” sense of normalcy that prevailed prior to the crisis because the coronavirus pandemic marks a fundamental inflection point in our global trajectory …. Radical changes of such consequence are coming that some pundits have referred to a “before coronavirus” (BC) and “after coronavirus” (AC) era. … (p. 12)

But then further down on the very same page Schwab’s confidence seems to flag, and he concedes suddenly that “by itself, the pandemic may not completely transform the world,” but might merely “accelerate many of the changes that were already taking place before it erupted.” Six pages later he reemphasises that “At the very least … the pandemic will accelerate systemic changes that were already apparent prior to the crisis,” but in the very next breath he’s talking of a clean rupture again, rhapsodising about “the possibilities for change and the resulting new order” which “are now unlimited and only bound by our imagination” (p. 18). Then in his conclusion, Schwab bizarrely decides that the virus isn’t even that dangerous; “the corona crisis is (so far) one of the least deadly pandemics the world has experience[d]” and “unless the pandemic evolves in an unforeseen way, the consequences … in terms of health and mortality will be mild” (p. 264f.) in comparison. The real source of reset is actually “today’s interdependent world” where “risks conflate with each other” (p. 247).

The problem is that Schwab can’t decide whether to hide in the motte or seize the bailey. Sometimes, he wants the pandemic to be a fundamentally new moment; other times, he’d rather make Corona contingent upon all the evil social inequities and climate imbalances and carbon unsustainabilities that are more his métier. The former position is more internally consistent and defensible, but it risks ceding too much space to a concept beyond Schwab’s concerns; the latter is deeply irrational but allows Schwab to make his favourite themes the explanation for everything.

It’s more than anything this indiscipline of thought that makes The Great Reset such an obnoxious reading experience. Schwab is always trying to have it both ways, he’s always forgetting what he just said a few paragraphs ago, he’s always wasting your time with irrelevant lists and details and descriptions that go nowhere. All too often, he loses all contact with concrete ideas and vanishes into a cloud of meaningless abstract terminology.

Why, for example, did these sentences have to be written?

A pandemic is a complex adaptive system comprising many different components or pieces of information (as diverse as biology or psychology), whose behaviour is influenced by such variables as the role of companies, economic policies, government intervention, healthcare politics or national governance … The management … of a complex adaptive system requires continuous real-time but ever-changing collaboration between a vast array of disciplines and between different fields within these disciplines. (p. 32f.)

Or this one?

Governments … have tools at their disposal to make the shift towards more inclusive and sustainable prosperity, combining public sector direction-setting and incentives with commercial innovation capacity through a fundamental rethinking of markets and their role in our economy and society. (p. 62)

These moments of exceptional pointlessness are everywhere in The Great Reset, and I have a small but growing collections of what I propose to call Schwabisms. These are brief statements that are so tautological, banal or bizarre that they ought to embarrass any author. Statements like “Everything now runs on fast-forward” (p. 7); or: “Complexity can be defined as what we don’t understand or find difficult to understand” (p.31); or: “If an observer can only make sense of ‘reality’ through different idiosyncratic lenses, this forces us to rethink our notion of objectivity” (p. 121); or: “Predicting is a guessing game for fools” (p. 126); or: “Many states that exhibit characteristics of fragility risk failing” (p. 127); or: “Dystopian scenarios are not a fatality” (p. 170); or: “In times of adversity, innovation often thrives – necessity has long been recognized as the mother of invention” (p. 232).

You have the feeling not only of a sad, small man, struggling to play the part of global governance guru, but of his equally pathetic audience of Hillary Clintons and Olaf Scholzes and Emmanuel Macrons, who hear this garbage and somehow manage to find it insightful and wish to be associated with it. What clouded intellectual lives all these people must lead.

In his bolder moments, Schwab argues that Corona only happened in the first place because the world didn’t embrace climate change and sustainability and stakeholder capitalism thoroughly enough. Schwab wants you to believe that we’re on the brink of a “global order deficit,” which we’ll need a “geopolitical reset” to remedy:

In this messy new world defined by a shift towards multipolarity and intense competition for influence, the conflicts or tensions will no longer be driven by ideology … but spurred by nationalism and the competition for resources. If no one power can enforce order, our world will suffer from a ‘global order deficit.’ (p. 104)

An interesting point is how much pessimism Schwab harbours about the future prospects of globalisation. He writes that “hyperglobalization” (whatever that is) “has lost all its political and social capital and defending it is no longer politically tenable” (p. 112f.), and that even normal globalisation is in decline. Thus politicians must strive “to manage” its “retreat” by making it “more inclusive and equitable,” as well as “sustainable, both socially and environmentally” (p. 112). These are curious admissions, and if you take them at face value, you’d begin to think that the Davos set really do feel under threat, especially from the left, and no small part of their political programme represents some kind of confused effort to appease imagined opponents.

Schwab writes that the pandemic happened because of “a vacuum in global governance” and because “international cooperation was non-existent or limited” (p. 115). He reveals a real childish yearning for “global governance” (p. 118), lest we end up “in a world in which nobody is in charge” (p. 114). The undercurrent of fear returns, and the pandemic recedes from view as a mere example of the kinds of disasters that will befall us if the globalist institutions fail:

There is no time to waste. If we do not improve the functioning and legitimacy of our global institutions, the world will soon become unmanageable and very dangerous. There cannot be a lasting recovery without a global strategic framework of governance… The more nationalism and isolationism pervade the global polity, the greater the chance that global governance loses its relevance. (p. 113)

Elsewhere, Schwab tries to construct Corona as contingent upon his favourite themes by suggesting that the mortality of the virus is exacerbated by pollution, which in his view raises “pandemic risk”:

We now know that air pollution worsens the impact of any particular coronavirus (not only the current SARS-CoV-2) on our health … In the US, a recent medical paper concluded that those regions with more polluted air will experience higher risks of death from COVID-19, showing that US counties with higher pollution levels will suffer higher numbers of hospitalizations and numbers of deaths. A consensus has formed … that there is a synergistic effect between air pollution exposure and the possible occurrence of COVID-19, and worse outcome when the virus does strike.” (p. 139)

Schwab is really, really straining here. First, there is the study in question, which is absolutely worthless because, as its authors admit, their “ecological regression analyses are unable to adjust for individual-level risk factors” and are thus “unable to make conclusions regarding individual-level associations.” These associations include things like “age” and “race.” At this point, you put the study in the garbage, OK? But it gets worse, because Schwab seems to think the paper is some kind of future projection, while in fact it’s a retrospective observational study. Wholly unsupported is Schwab’s final adventurous suggestion, that via a hocus-pocus “synergistic effect” pollution might somehow bring about virus infections. Many, many moments of The Great Reset are like this—as soon as you start picking at them, the whole thing falls apart.

A final awkward struggle to place Corona downstream from sustainability failures comes when Schwab declares that, according to Science, it is environmental destruction that is the true cause of pandemics:

By now, an increasing number of scientists have shown that it is in fact the destruction of biodiversity caused by humans that is the source of new viruses like COVID-19. These researchers have coalesced around the new discipline of “planetary health” that studies the subtle and complex connections that exist between the well-being of humans, other living species and entire ecosystems, and their findings have made it clear that the destruction of biodiversity will increase the number of pandemics. (p. 137)

Set aside Schwab’s recurring genius for getting things wrong—it’s not the “destruction of biodiversity” that is proposed to be “the source of new viruses,” but the increasing proximity of human populations and animal reservoirs. No, the more interesting point here, is how uninformed Schwab reveals himself to be, in his total neglect of the phoney pangolin thesis of Corona origins. By mid-2020, the topic had been all over the news, and yet word of it somehow escaped Schwab, who in consequence misses a whole argument tailor-made for his tedious morality tale. He could’ve regaled us with paragraph upon paragraph about how only global governance can suppress the trade in endangered species and save of us from deadly pangolin viruses, but instead he went for this weak tea, because he has no idea what he’s talking about.

Deep down, Schwab doesn’t expect his readers to buy that the pandemic happened because we haven’t made appropriate sacrifices to the ESG idols. So he offers the alternative position, that Corona isn’t so much contingent upon environmental and sustainability catastrophe, as it is the same kind of catastrophe, or at least so thoroughly interconnected with these other potential catastrophes that it might as well be the same thing:

[I]n global risk terms, it is with climate change and ecosystem collapse … that the pandemic most easily equates. The three represent, by nature and to varying degrees, existential threats to humankind, and we could argue that COVID-19 has already given us a glimpse, or foretaste, of what a full-fledged climate crisis and ecosystem collapse could entail from an economic perspective … The five main shared attributes are: 1) they are known … systemic risks that propagate very fast in our interconnected world and, in so doing, amplify other risks from different categories; 2) they rae non-linear, meaning that beyond a certrain threshold, or tipping point, they can exercise catasrophic effects; 3) the probabilities and distribution of their impacts are very hard, if not impossible, to measure …; 4) they are global in nature and therefore can only be properly addressed in a globally coordinated fashion; and 5) they affect disproportionately already the most vulnerable countries and segments of the population. (p. 133f.)

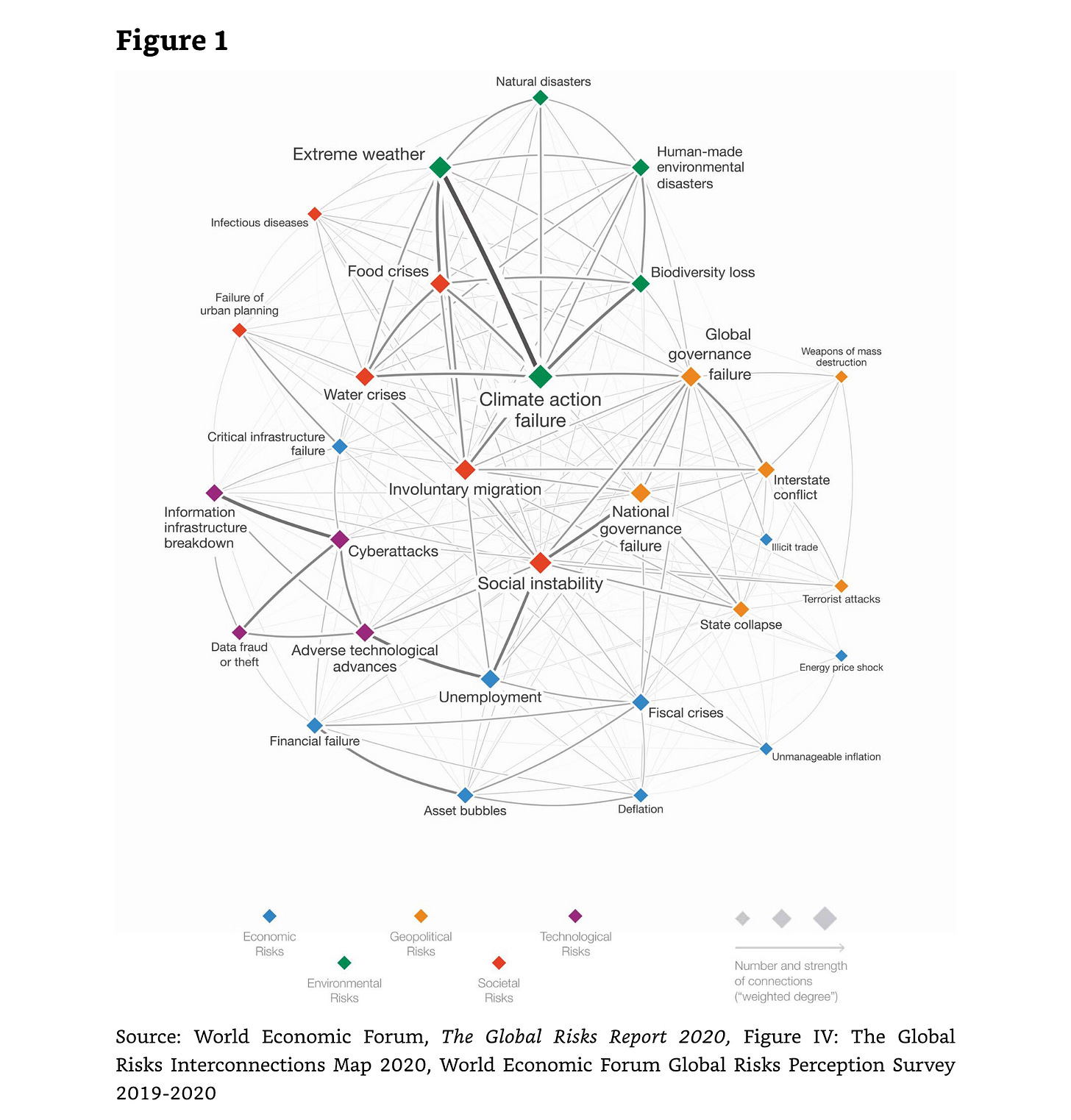

Schwab even includes a totally meaningless chart to illustrate his beloved hyperconnectivity thesis, via which everything automatically becomes about everything else:

Clearly, very little actual thought went into this graph. You can tell by looking for things that aren’t connected but should be—for example, there’s no line connecting “weapons of mass destruction” to “human-made environmental disasters,” although probably no “human-made environmental disaster” has been more eagerly contemplated than nuclear winter. Schwab is mainly interested in providing his readers with an academic aesthetic and the feeling that they’re reading something sophisticated and learned, even though they aren’t.

At least we’re not getting climate lockdowns. Schwab is disappointed by projections that the Spring 2020 restrictions would reduce carbon emissions by only 8%:

Considering the severity of the lockdowns, [that] figure looks rather disappointing. It seems to suggest that small individual actions … are of little significance when compared to the size of emissions generated by electrictiy, agriculture and industry … Even unprecedented and draconian lockdowns with a third of the world population confined to their homes for more than a month came nowhere near to being a viable decarbonization strategy because, even so, the world economy kept emitting large amounts of carbon dioxide … (p. 140f.)

Again, one is just struck over and over by Schwab’s apparent ignorance and naiveté, even on subjects at the centre of his expertise. People have long demonstrated that curbs on individual consumption, particularly in the West, will have very limited effects on environmental outcomes. Most emissions come from overseas manufacturing.

So far I’ve tried to focus on Schwab’s core ideas, to show why they’re nonsense even on their own terms. Schwab is wrong about a lot of other things though, and there’s some real howlers in these pages. There is his apparently earnest belief that “the post-pandemic era will usher in a period of massive wealth redistribution, from the rich to the poor and from capital to labour” (p. 77). When you’re done laughing, you’ll see that the statement rests on superficial historical comparisons to things like the Black Death, which drove up the cost of labour by killing millions and millions of peasant farmers and artisans. Schwab can’t see that there’s no equivalence between a plague that kills 40% of the European population and a virus with at best a 0.4% IFR, with deaths concentrated almost entirely in the retired elderly. That’s how stupid he is.

Then there’s his strange attempts to make the pandemic responsible for the Floyd riots, and his recurring assertion that “the greatest underlying cause of social unrest is inequality” (p. 88)—ignoring the clear historical pattern that it is liberalising reforms and rising expectations which spark social uprisings. And there’s his repeated insistence that nations which are “perceived as providing a sub-par response to the pandemic” (p. 98) may face a legitimacy crisis, and “that many governments will be taken to task, with a lot of anger directed at those policy-makers and political figures that have appeared inadequate or ill-prepared in terms of their response to dealing with COVID-19” (p. 76). All that’s happened since Schwab wrote, of course, is the steady repudiation of mass containment, which every day grows more open.

Schwab is not only wrong; he’s also a creep, but I’m far from the first to notice, and there’s little point in going very far into this aspect of The Great Reset. He eagerly contemplates the possibilities of mass surveillance and has an obvious hard-on for contact tracing apps, perhaps the most openly discredited containment measure of all. He writes happily that the pandemic has given governments “the upper hand” and hopes that “Everything that comes in the post-pandemic era will lead us to rethink governments’ role” (p. 91). He also approvingly cites the theories of economist Dani Rodrik, according to which “economic globalisation, political democracy and the nation state are mutually irreconcilable” (p. 107)—embracing the uncomfortable implications that his programme comes at the cost of national government and our parliamentary institutions.

Some might dispute that The Great Reset is an attempt to pivot back to stakeholder capitalist climate change, rather than an embrace of lockdowns and virus hysteria, but I promise that this is the message of the book. In his private correspondence with WEF conference attendees, Schwab was even more explicit on this point, informing the Dutch Minister of Finance that his goal for the 2020 conference was to set the stage for sending “a clear signal, at the beginning of next year, that the world has moved out of the COVID-19 pandemic.” Yet nobody declared the pandemic over in 2021, and from that you may take some measure of the true influence that our globalist guru exercises over the affairs of national governments.

Ultimately, Schwab’s importance is elusive. I’d suggest he’s mostly a vessel for the goals and the ambitions of the political and corporate leaders who orbit the World Economic Forum. He’s a bad thinker and a lazy intellect, but he’s good at telling these people what they want to hear, and this makes him an interesting window onto their fears, beliefs and tendencies. The careless and under-digested nature of his analysis seems powerfully metonymic for the attention deficits and abbreviated time horizons that characterise the elite political outlook. It’s also worth noting that there’s a lot of uncertainty and anxiety in these pages—about social unrest that might be sparked at any moment by vague abstract things like inequality, about nebulous climate disasters that might be sparked at any moment by not being ESG enough, about the pandemic and its management that might at any moment fly out of control, and about how far politicians might go in their repressive solutions to all these ticking time bombs.

One of the few things I’ve understood better after reading this dreck is the significance of climate change for globalising institutions. Sustainability concerns are important because they’re the archetypal crisis that cannot be solved without “global coordination.” Combatting climate change is the thing global institutions are supposed to coordinate, and without which they begin to lose most of their justification, because nobody has been able to come up with very many other problems for them to solve:

In the face of … a vacuum in global governance, only nation states are cohesive enough to be capable of taking collective decisions, but this model doesn’t work in the case of world risks that require concerted global decisions. The world will be a very dangerous place if we do not fix multilateral institutions. Global coordination will be even more necessary in the aftermath of the epidemiological crisis, for it is inconceivable that the global economy could ‘restart’ without sustained international cooperation. (p. 118)

Emphasis mine. Schwab desperately wants Corona to the be same kind of crisis as climate change, because by profession he’s only interested in problems that require supernational levels of coordination. Too bad for him, that’s not how the pandemic worked out. Global institutions had no more than a minor role to play in the pandemic response; the prime movers were in every case national bureaucracies. Schwab and company have spent their whole lives trying to get everybody up in arms about global warming, but they’ve never come close to realising the enthusiasm and bureaucratic buy-in that mass containment achieved in the space of a few weeks. The Great Reset is nothing but a 300-page attempt to cope with this awkward reality.

The Davos crowd see themselves as post-ideological, technocratic problem-solvers, but it’s impossible to deny that some kind of abstruse, malformed ideological system pervades Schwab’s work. It might be too ungainly and broken to acknowledge or defend, and it’s remarkably hard to describe, but it’s there. Postwar optimism and the generations of uninterrupted technological progress that followed, encouraged some people to believe that we were on the verge of a new world, one where a utopian global order would supplant both nation states and corporations, ushering in a post-capitalist, post-nationalist era, where all our most pressing problems would be solved. Yet the nations states stayed around, for-profit businesses are still here, and technological progress has stalled. What remains is a lot of jargon and vacuity, signifying nothing.

"I have a vision of Schwab in his study, typing furiously with extended index fingers like a bicephalic chicken, marshalling all his meagre powers to reconstruct the very unexpected pandemic in which he found himself..."

This is goddamnned poetry! I can't get the image out of my head now.

History will not be kind to this period in our collective cultures. Decisions made around Covid will be laughed at, cried over or shouted down but none will be celebrated. None. Until then, all I can say is Pray, Plan, Prepare and RESIST.